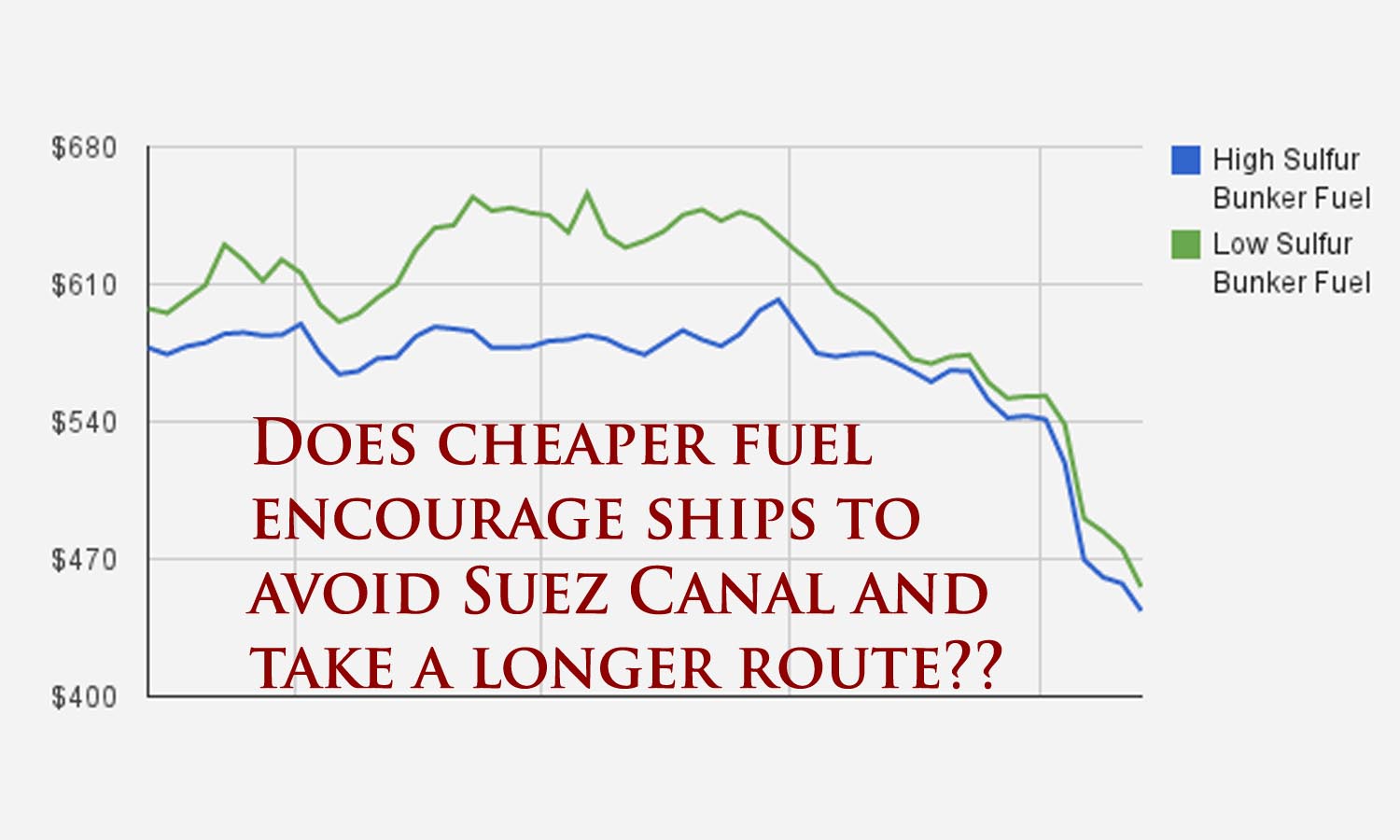

The changing shipping trend of avoiding the Suez Canal and taking the longer route around the Cape of Good Hope has been made possible by the plummeting oil prices in the international markets.

Since the time it was found that a shipping passage could be made between the Red Sea and the Mediterranean Sea by carving a canal between Africa and Asia, the shipping companies and international traders had remained ever hopeful. Such a passage would not only reduce travelling distance, but would also save on fuel and time.

Suez Canal – the saviour

This fervent wish of shipping companies and traders came to fruition when work began on building a canal to link the two seas. Started in 1859 in Egypt, from Port Said in the north and Suez in the south, the construction of this 193-kilometer (120-mile) long canal was an amazing engineering feat. It took years and many lives to complete and was eventually thrown open to ships in 1869. The peculiarity of this canal is it does not require locks, since the builders utilized several lakes located along the way, from north to south, to chart its route.  Separating the Asian continent from Africa, this canal provides the shortest maritime route for ships going towards Europe from the Indian and western Pacific oceans and vice versa, obviating the need to circumvent the Cape of Good Hope. The canal, an Egypt-owned entity, revolutionized trade. Little wonder till today this canal witnesses one of the world’s heaviest shipping traffic. There are clear advantages of using this canal. For example, it saves nearly 3,500 nautical miles (6,480 kilometers) for a ship travelling from Singapore to Rotterdam in the Netherlands. And this translates into saving a lot of time and money.

Separating the Asian continent from Africa, this canal provides the shortest maritime route for ships going towards Europe from the Indian and western Pacific oceans and vice versa, obviating the need to circumvent the Cape of Good Hope. The canal, an Egypt-owned entity, revolutionized trade. Little wonder till today this canal witnesses one of the world’s heaviest shipping traffic. There are clear advantages of using this canal. For example, it saves nearly 3,500 nautical miles (6,480 kilometers) for a ship travelling from Singapore to Rotterdam in the Netherlands. And this translates into saving a lot of time and money.

Suez Canal – the downside

Today, Suez Canal Authority certainly cashes in on the ships using it. There is a steep fee for using this canal. According to Maersk, they have to shell out approximately $350,000 per ship and this is just the initial cost. Every year, ships spend several billion dollars just to get the privilege of using the canal. In addition, the ships have to mandatorily take on a Suez crew for the duration of the transit. According to the users, there is just no requirement of such a crew, as the ships passing the canal are well versed with the route. All the Suez crew members do is to loll around on the ship and sell souvenirs. Not only this, often the ships are levied a cigarette ‘tax’, which may cost upwards of $560 per ship.

The changing scenario

Up until now, there was hardly any choice but to use the canal, since it was considered vital for global business. However, things are changing now. A cheaper alternative to Suez Canal has slowly emerged and that is by again taking the longer route! Surprisingly, it is the plummeting cost of fuel that has made this alternative viable. ‘Bunker fuel’, a thick heavy fuel that is used by ships has become affordable enough for ships to take longer routes to their destinations, altogether avoiding the Suez Canal. If the ships are saving on Suez Canal fee and taking the longer route due to cheaper fuel, what about the time taken for such journeys? According to Maersk it only takes 11 days more for a ship, travelling at 13.5 knots, to go via the Cape which is time efficient.

Cheaper fuel, better trade opportunities

Till the time the oil remains cheap, ship owners will retain the choice of taking whatever route they want. In fact, going around the Cape of Good Hope may turn out to be a profitable proposition for them.

These ships can choose to be at sea longer and stop at the ports in Asia, Africa and Europe to shop for unsold cargo. This cargo can then be sold at a premium to the right buyer at the right time. However, for this the ship should be able to dock at the given port, that is, should be of the right size. And the products they sell must meet the demands of the local markets. On the flip side, if they fail to find the right buyer, they can lose money too. But, ships look keen to take the additional thousands of miles of detour in the hope of making the trip profitable.

Tricky economics of oil markets

So, are we to believe that this is a welcome move by the world over? Not exactly. There is a tricky economics of oil markets. Although, currently the world is inundated with an oversupply of crude oil, oil traders are resorting to hoarding, which is called a ‘contango’. These oil traders are storing oil and refined oil products at sea or in storage, even though more crude oil is available than needed. There is also a high demand for refined oil products, like gasoline. This is being done in the hope that prices may rise again.

Oil traders are hoarding oil and refined oil products waiting for the prices to rise again

This artificial scarcity of oil has made the market extremely volatile and has allowed the oil traders to cash in on this oil crunch by raising the prices of crude and oil. Such unscrupulous traders are under the lens of the maritime authorities and at present the focus is on half a dozen diesel and jet fuel carrying ships plying on this very route.  The common excuse of these oil-laden ships to stay out at sea for prolonged periods is that their cargo is not completely sold and they need additional time for the same. Such ships, termed as ‘floating storage’, are also anchored offshore simply waiting for the market to turn favourable to offload their crude and oil at higher prices. According to the authorities, the numbers of such ‘floating storage’ ships have increased manifold. In December 2015, it hit a five-year high that continues to remain so.

The common excuse of these oil-laden ships to stay out at sea for prolonged periods is that their cargo is not completely sold and they need additional time for the same. Such ships, termed as ‘floating storage’, are also anchored offshore simply waiting for the market to turn favourable to offload their crude and oil at higher prices. According to the authorities, the numbers of such ‘floating storage’ ships have increased manifold. In December 2015, it hit a five-year high that continues to remain so.