It’s one of the freezing, darkest point on earth, full of aquatic life – a gigantic part of which is yet to be ascertained – with a seabed rich in mineral deposits.

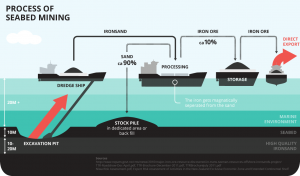

In the past 10 years, the base of the deep ocean that lies farther the jurisdiction of any one country has been progressively examined. Several parties are surveying over the mineral extent that can be utilized as raw materials for batteries and jet engines to wind turbines and the cell phones. In countries like Japan and Papua New Guinea where the Solwara 1 mining project was grounded came to a hault. 2019 will see an analytical global projects and discussions on how to manage the resources in the international waters. The UN appointed body, International Seabed Authority is held responsible for looking after the “common heritage of mankind”. The treasure hidden inside the deep dark and cold seabed.

The ISA’s 168 representatives must ponder upon how to protect this feeble and rare ecosystems. This is a multibillion dollar business, which needs to work upon the assertion of the profit sharing equally, accountability and transparency. The ISA has granted 29 exploration contracts of 15 years three kinds of deposits over 1.3 million square kilometers of seabed in the Pacific, Indian and Atlantic oceans. ISA has two vital meetings in February and July respectively, in Kingston, Jamaica, to conclude with its code and meet its deadline of 2020.

A few civil society associations and scientists discuss that the world’s ocean is already severely stressed from climate impacts and overfishing, and that regulations are being developed without a full understanding of the risks.

The deep sea mineral formations contain a number of highly prized metals, including copper, zinc, manganese, cobalt and rare earth elements. The poly metallic nodules, consisting mainly of manganese, are bumpy, usually potato-sized balls suspended in mud on the floors of the deep abyss. They are found in an exploration zone of the eastern Pacific known as Clarion – Clipperton. This is the field of greatest commercial interest, predicted to hold more nickel, cobalt and manganese than all known terrestrial deposits combined. A recent MIT cost-benefit analysis found that mining these growth would be profitable, with an annual revenues of up to US$2.2 billion a year.

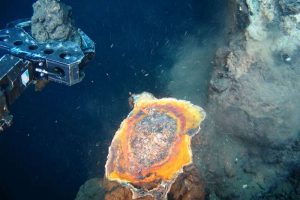

Polymetallic sulphides are developed throug h hydrothermal action when hot water, released from the earth’s crust, hits the cold water and deposits a “pile” of minerals including iron, silver and gold. These vents look like smokestacks, and are mostly placed on the top of steep, semi-active volcanoes deep in the Pacific and Atlantic. Cobalt crusts are found on underwater mountains, mostly in the Pacific, at depths of 400 to 7,000 metres, and include limited earths.

h hydrothermal action when hot water, released from the earth’s crust, hits the cold water and deposits a “pile” of minerals including iron, silver and gold. These vents look like smokestacks, and are mostly placed on the top of steep, semi-active volcanoes deep in the Pacific and Atlantic. Cobalt crusts are found on underwater mountains, mostly in the Pacific, at depths of 400 to 7,000 metres, and include limited earths.

So far, 29 exploration contracts have been granted to joint private entities sponsored by national governments, including China, Germany, India, France, Japan, the Republic of Korea, the Russian Federation and the lnteroceanmetal Joint Organization (a consortium of Bulgaria, Cuba, the Czech Republic, Poland, the Russian Federation and Slovakia), as well as small island states like, the Cook Islands, Kiribati, Nauru, Singapore and Tonga.

China, the world’s largest buyer and shipper of minerals and metals, is a very influential party, with the maximum contracts, as per Conn Nugent, director of the Pew Charitable Trusts Seabed Mining Project, which is demanding for a “precautionary” mining code. “National prestige is at stake here. Xi [Jinping] has the ‘three deeps’ – deep space, deep earth, deep Ocean. And that shows they are going to be adding several resources into this.”

| Seabed Mining Sponsoring State | Contractor |

| China | China Minmetals Corporation |

| Cook Islands | Cook Islands Investment Corporation |

| UK and Northern Ireland | UK Seabed Resources Ltd. |

| Singapore | Ocean Mineral Singapore Pte Ltd. |

| Belgium | Global Sea Mineral Resources NV |

| Kiribati | Marawa Research and Exploration Ltd. |

| Tonga | Tonga Offshore Mining Limited |

| Nauru | Nauru Ocean Resources Inc. |

| Germany | Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources of Germany |

| India | Government of India |

| France | Institut français de recherche pour l’exploitation

de lamer |

| Japan | Deep Ocean Resources Development Co. Ltd. |

Once the code is agreed, seabed mining would not necessarily start with immediate effect. Under ISA draft rules, contractors will have to undertake an environmental impact assessment and demonstrate financial and technological capacity. The Belgian firm Global Sea Mineral Resources says it is ready to start as early as 2023. Observers foreseeing anything from 2025-27, while others question whether the “geologists’ fantasy” will get off the ground at all.

Meeting Demand

While there have been a few failed efforts to exploit these minerals, there are reasons why the recent phase of exploration could succeed. It comes down to demand from a growing, resource-desirous population. What we are witnessing these days is a much bigger market, thanks to more widespread industrialization which is directly linked to a reduction in world poverty,” says John Parianos, chief geologist of Nautilus Minerals.

Estimates differ, but if mineral demand were to raise at the predicted 1% annual rate, it would be about 60% higher by 2050. For specific commodities such as copper, there could be up to a 341% rise in demand. The ISA says that up to 15% of global demand for copper and nickel could be achieved from the deep seabed.

At the same time, land-based deposits of metals have become more challenging and less profitable to extract. Cobalt is mined almost exclusively in the Democratic Republic of Congo, one of the indigent, most violent and corrupt nations in the world.

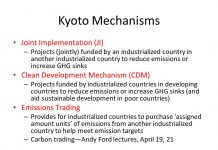

The promoters of deep sea mining argue that it could offer – in far richer concentrations than that found on land – a reliable, clean and ethical source of the raw materials that are critical to high-tech and renewable energy technologies.2016 supply and demand review was wrapped up as the most ambitious scenario – 100% renewable energy by 2050.

The projected demand could be met by existing terrestrial mining, improved metals recycling, and more. “Deep sea mining promotes the belief that you can continue unparalleled growth, but in different ways,” says Andy Whitmore, of the Deep Sea Mining Campaign (DSMC), a coalition of NGOs and local people from the Pacific, Americas and Canada opposed to mining.

Conflict of interest

Any capital made from eventual mining will be subject to a benefit-sharing regime and shared among member states, taking into account the needs of developing nations. The payment regime is still being thought-up, and the ISA has contracted MIT to analyze a number of economic models.

“Countries are starting to realize that even a dozen or more mining operations aren’t going to pay a lot in royalties if it’s divided by the 167 nations plus the EU. But they can make potentially good money by being a so-called sponsor state where they levy the mining company directly,” said Gianni. This conflict of interests’ analysts. It’s deeply troubling that the ISA is creating the rules at the same time as making capital out of the rules it creates,” said Whitmore.

The tie-ups between the companies and the nations sets up unhealthy situations in terms of transparency and accountability. Even with the best regulations in place, if the economics are adequately strong to drive this industry forward, it’s going to be extremely difficult to say no to a country who wants a contract.

Once the door is opened one has the potential to have runaway development for mining of the deep dark ocean over hundreds of thousands of kms and the ISA will have very less tools in its chest to constrict that industry.