What do you think happens to ships that have completed their lives, have grown beyond economical repairs or have become unprofitable to operate? No, they are not abandoned in some remote nameless island or atoll to rust and rot. Instead there is a whole industry that thrives on dismantling such ships.

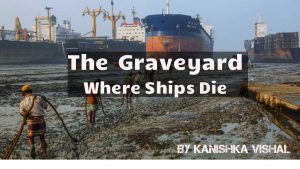

Popularly known as ship graveyards, the ship-breaking or demolition forms part of one of the four sub-markets of the shipping industry – freight market, shipbuilding, ship-breaking and second-hand market.

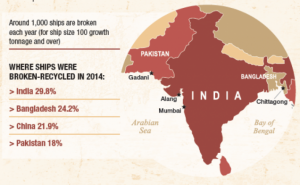

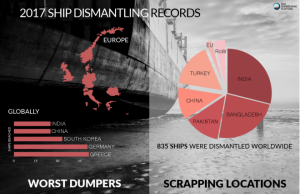

On the forefront of this business are developing countries like Bangladesh, China, India and Pakistan, where 82 percent of world’s ship-breaking activity, in terms of number of ships, takes place and where 92 percent of Dead Weight Tonnage (DWT) gets demolished. And it is easy to guess why…cheap labor and almost non-existent environmental norms.

India rates high in this business, since it has beaches with an ideal 15-degree slope and coastlines free of mud that makes them ideal for ships to beach easily. Ship graveyard, called the ‘ship recycling site’, is where the process of breaking down a ship takes place.

Breaking a ship

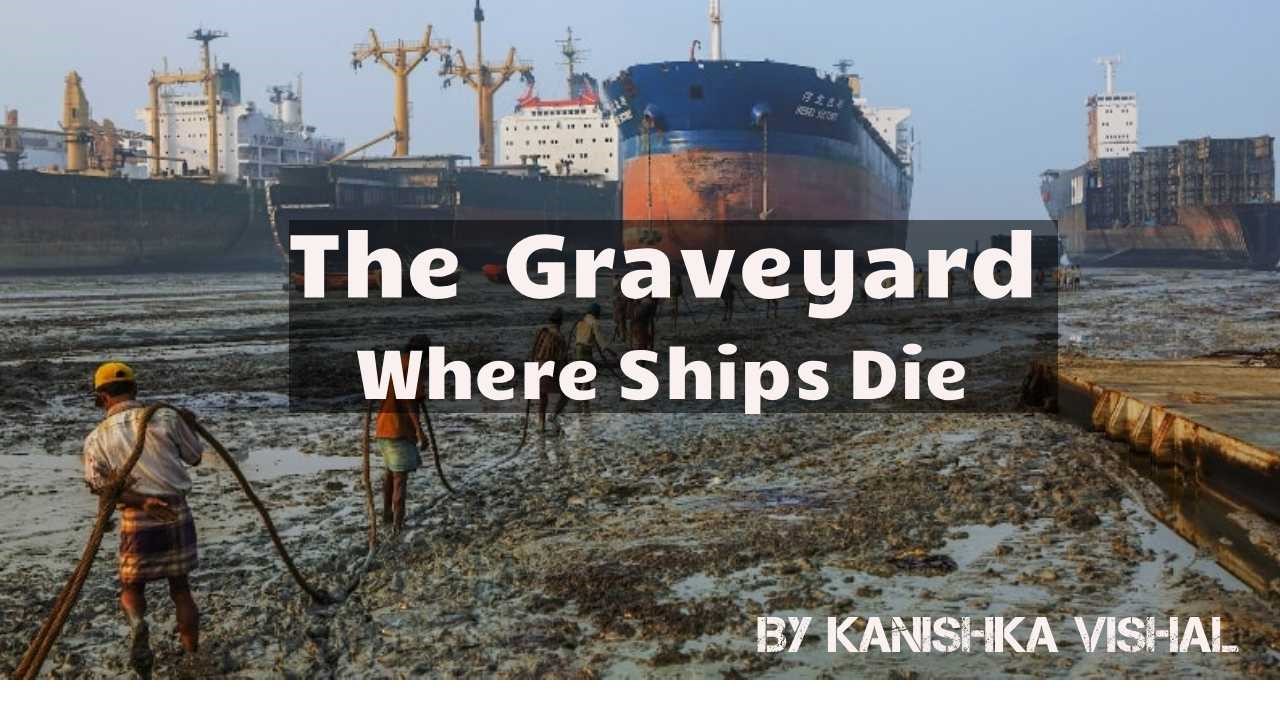

A visit to Alang, one of the biggest ship-breaking yards in Gujarat, India, or the one in Chittagong, Bangladesh, presents an unsettling view. The entire beach is littered with iron sheets, iron angles, windows and all that could be salvaged from a ship. The site may give an impression of total chaos, with a medley of cranes, cables, trucks, workers, cutters adding to the heat and dust, and accompanying cacophony.

However, there is a method to this madness. When a ship has completed its life tenure, usually of 30 years, it is brought to a ship-breaking yard, where it is beached under guidance and anchored.

The first step in dismantling is to drain the ship of its remaining diesel fuel, engine oil and other chemicals. This done, it is then stripped of all parts that can be reused in new ships or sold in the local market, such as electrical wiring, plumbing, wooden furniture, machinery, etc.

It is then that the real ship-breaking begins. The master cutters, experts in precise stripping of a ship, strip off the outer steel skin covering the hull and the body of the ship with blowtorches, steel panel by steel panel, till there is nothing left. The aim is to break down a ship in the least possible time and with the least risk to workers. This way, almost 90 percent of a ship is broken down and recycled.

What is surprising is there is no written procedure for reducing a ten-storey high steel hulk of a ship to scrap. It is done at the discretion, judgment and hands-on experience of supervisors and workers who have acquired practical skills over the years in business. It comes as no surprise that it takes anywhere from three to six months to completely break a ship, depending upon its size.

Regulations for dismantling a ship

Since dismantling a ship is regarded as one of the most dangerous professions in the world, it is not without regulations. It follows the Hong Kong International Convention for the Safety and Environmentally Sound Recycling of the Ships, 2009. This primarily ensures the health and safety of personnel involved in ship-breaking and the preservation of the environment.

Then there is the Basel Convention, involved in handling the ship disposal issues that addresses safe disposal of hazardous substances, such as asbestos, PCB and waste oil products. Although this convention has been signed by 116 nations, there is no mechanism to enforce the guidelines. The convention has now roped in the International Maritime Organization (IMO) for framing improved rules and regulations regarding these issues.

In developing countries, these conventions are not followed in letter and spirit, thereby making them most ideal and cheapest ship graveyards. In India, the Supreme Court has now created safety guidelines for the industry. However, the risk of death and injury remain, and the workers continue to work for paltry wages. Despite this, the workers remain upbeat, as one cutter succinctly puts it, “The ship dies, so we can survive.”

The ship-breaking dilemma

If you think shipowners automatically take their ships, that have lived their lives, to ship graveyards to be dismantled, you cannot be more wrong. The owners of these tottering old ships are most reluctant to do so, since in their twilight years too these ships remain profitable cash cows.

The attraction of higher freight rates tempts the owners to press their aged, inefficient and technologically obsolete ships into service and makes them reluctant to sell it for scrap. This leads to an intriguing dilemma.

On the one hand, the greed for making a neat packet from obsolete vessels reduces the number of such ships to be scrapped. On the other hand, the burgeoning demand for scrap steel used in the steel production process makes selling a ship for scrapping lucrative.

Negotiations involved in ship-breaking

When the shipowner finally decides to scrap his old ship, he approaches one of the ship-breaking yards that usually line the coasts in developing countries. Incidentally, almost 120 ship-breaking yards dot the Alang coast and 80, the Chittagong coast.

The deal is struck between the shipowner the owner of the ship-breaking yard. In this, a cash buyer usually acts as an intermediary, since most shipowners prefer cash payments. It is the cash buyer who facilitates this by purchasing the ship in hard cash on ‘as is where is’ basis. For this, he offers a small advance and a bank letter of credit with validity between 60 to 180 days to the shipowner.

Thus, the cash buyer becomes the temporary owner of the ship for a small period of time, till he negotiates its sale with the ship-breaker, usually against a bank letter of credit. Thus, a cash buyer is an indispensable financial facilitator in the whole process.

The cash buyer takes on the financial risk arising due to the time lag between cash payment and selling of the ship to the ship-breaker. The currency exchange fluctuations also cause additional risk for him, as also the payment for the ship using the letter of credit by the ship-breaker.

The initial cash transaction is carried out in US dollars, where the ship-breaker pays for the ship to either the shipowner or the cash buyer. For the shipowner, this payment is the biggest cost of scrap steel production.

The second cash transaction usually covers the cost of the ship-breaking process, such as labor, taxes, financial costs and consumables, which are paid locally. In the third and final cash transaction, it is the scrap steel buyer who pays the ship-breaker for the scrap steel.

The currency in which this transaction takes place depends upon the buyer. If he is a local, the transaction is in local currency, if foreign, in US dollars.

For the ship-breaker, the flow of cash both in US dollars and local currency and the fluctuating exchange rate of the foreign currency affects not only his profitability, but also the financial costs of the letter of credit issued for the purchase of the ship.

Is ship-breaking profitable?

How much do you think ship-breakers make per ship? Although they are wary about committing anything, it can be anything around US$1 million in profits alone on an investment of US$5 million in buying the ship. The figure depends upon the size of the ship dismantled, the current price of steel, and other factors.

With such large figures and skilled workers earning a mere Rs.500 for a 10-hour daily shift in India, ship-breaking, despite all the monetary risks, still comes across as a profitable business for all.

The risks involved in ship-breaking to the health of workers and to the environment is offset by the creation of jobs for thousands. Not only is this industry profitable for the ship-breaking yard owners, but is also a significant foreign exchange earner for the developing countries. However, there is a need to implement the conventions to make this business safe for both workers and the environment in the developing countries.